What does Wabanaki stewardship look like?

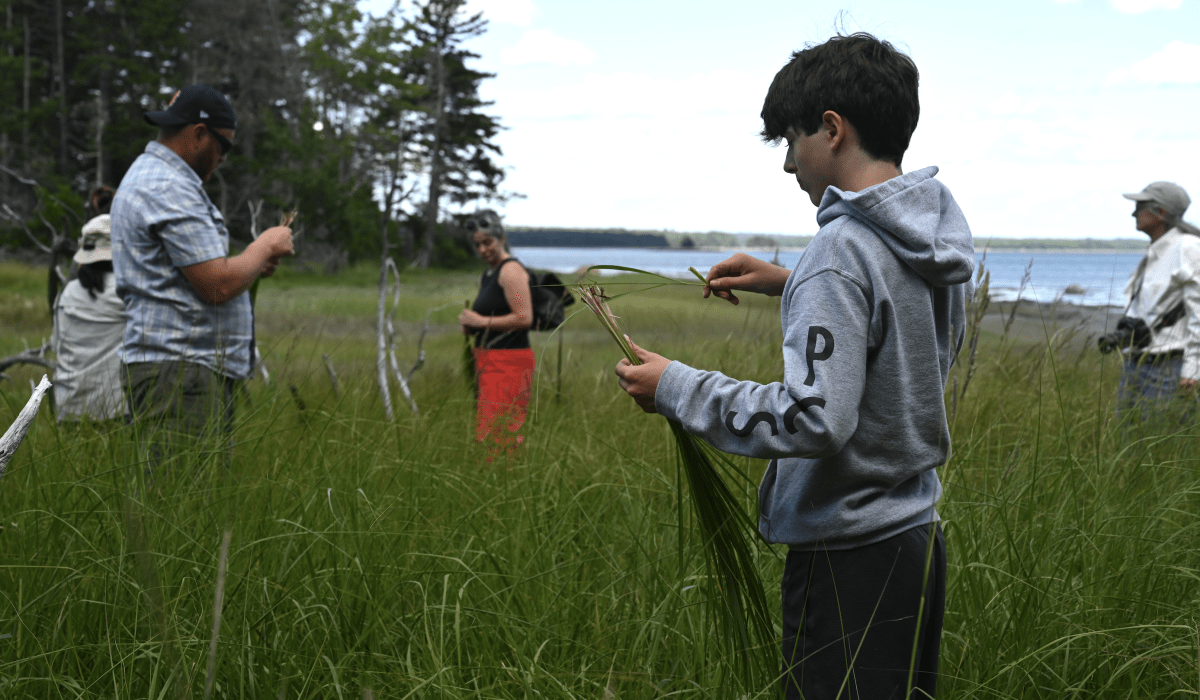

We’re relearning what land looks like when it's cared for by Wabanaki communities.

By Brett Ciccotelli, Ellie Oldach, and Peter Forbes

August 08 2023

Today, land trusts own and manage large portions of the Maine landscape. As a result, many people understand what land trust stewardship looks like—bog bridging, trail signs, forever farm fields, conserved woodlands, water access, and the like.

Meanwhile Wabanaki stewardship, though the predominant human touch on this landscape for over 10,000 years, can be harder to see. Centuries of colonization, oppression, and erasure have minimized the parts of this landscape that are in direct Wabanaki care and stewardship. On the roughly 1% of Maine that is currently owned by Wabanaki people, this stewardship can take many forms.

Here are some examples of what we see on Wabanaki-stewarded land:

A basket maker harvests a brown ash tree, opening the forest canopy and letting in light that helps smaller ashes grow wide, white rings for use in future baskets.

Wabanaki-led natural resource departments plan and hire local contractors to bury tree roots and boulders into riverbeds, restoring fish habitat for salmon and brook trout.

Ambassadors and elected officials fight for recognized sovereignty and self-determination at the Maine State House.

Wabanaki leadership restores a reclaimed superfund site along a river into a gathering space and a pathway lined with tall river birches, rebuilt atop an ancestor’s village.

In rural Maine, a tribe builds a new football field that brings high school football back to the neighboring community.

A tribal-run and -staffed farm grows crops and raises fish to feed all the families of their Nation, stock local ponds, and share the surplus with the neighbors.

Wabananki-led timberland management focuses on building stable roads and bridges, supporting forest health, sustaining moose populations, and creating opportunities for community access.

Tribes lead the Penobscot River Restoration Project, where thousands of miles of the Penobscot River are reopened to sea-run fish species.

Game wardens and hunting guides protect and provide hunting and fishing opportunities for both Tribal and non-Tribal citizens.

Tribal members at the University of Maine lead the work to protect Ash trees from the emerald ash borer.

Tribal representatives in Augusta advocate for strict water quality standards that would make sustenance fishing safer for both Tribal and non-native communities.

Tribal natural resource companies produce maple syrup and blueberries.

Across the territory, Wabanaki-led non-governmental organizations provide space for learning and healing, support safe and affordable housing for Wabanaki people, teach youth how to carry forward two-eyed seeing, and offer places for the community to come together around land.

Wabanaki land stewardship helps us all remember that the work of caring for the earth and recovering land is not new to this moment, but a role carried forward.